By Kirk Haaland of enCYCLONEpedia.comFollow Kirk on Twitter @khaal53

If every trip down the court resulted in a layup or dunk for a team’s best close range shooter, all of this would be moot. However, we all know that isn’t reality.

Much has been made of this year’s Cyclone basketball team and the shot selection of a few and the team as a whole. In reality, Iowa State scores the fifth most points per possession in the conference on the season with 1.09 pts per possession (just behind Kansas and Texas at 1.10), so it really can’t be that bad, can it?

While the answer to that is most likely “yes,” the details would show that the offense could still be much better with an improved shot selection. When a team shoots as many 3-pointers as Iowa State does fans are bound to say, “Stop shooting so many threes!” Many times those comments are made regardless of offensive success as a whole.

Shot selection is the fight that coaches have been waging war on with their players since the beginning of time. Coaches by nature try to shape and mold players to just play basketball instinctively but to do it making the smartest decisions possible. In my opinion, the fruits of that are most evident with a player’s shot selection.

The contributing factors to how a shot is classified has many variables, from who is taking the shot, to what is the game and time situation, to how is the game flowing, and on and on. A lot of these factors dictate that classifying a given shot as good or bad to be a matter of “feel” for the game at the time and thus making stats and numbers less supportive.

In other words, it is very subjective trying to characterize each and every shot that gets hoisted up as good, okay, or bad. Granted there are the shots that draw obvious conclusions like a fast break dunk or layup or a shot early in the shot clock with the lead late in the game over an in-state team that wears purple—ahem, LaRon Dendy—but it is the everything in between that is the most difficult to label.

With a risk of this commentary becoming a circular reference for each variable let’s try to proceed one variable at a time…

Shooting percentages

Perhaps it is common knowledge or perhaps it needs to be said, but I will say it anyway to help separate the quality of shot between a 3-point shot and a 2-point shot; for reference sake, shooting 33 percent from the 3-point line is basically the equivalent to shooting 50 percent from 2-point range. If you make 33 percent of 100 attempted 3-pointers you have 99 points and if you make 50 percent of 100 attempted 2-pointers, you have 100 points.

That is why effective field goal percentages are so useful—it gives the value of a 3-pointer the extra 50 percent that it is worth. The players that shoot a high percentage from inside the arc will still be expected to have a higher percentage, just as they do with field goal percentage, but if you make 3-pointers at a rate better than 33 percent then you’d essentially be outshooting all of the players that shoot less than 50 percent from 2-point range.

Of course, all 2-point shots and 3-point shots are respectively not created equal. A 16 foot fade away jumper is going to be made at a lower percentage than a wide open layup.

The quick shot

I didn’t play college basketball so I never experienced the shot clock but if I had a dime for every time I heard my high school coach say, “if you can get that shot after three passes you can get it after 13 passes.” Meaning you can’t maximize a possession if you don’t work the ball around, move through your offense, or run your called play.

There are always the extenuating circumstances to get an early shot if it is a good look. Scott Christopherson taking a wide open 3-pointer with 25 seconds on the shot clock is something I would approve. Melvin Ejim taking a wide open 3-pointer with 15 seconds on the shot clock is more iffy. That’s what happens when you compare a 41 percent 3-point shooter to a 19 percent 3-point shooter.

That isn’t to say that Melvin Ejim should never shoot a three ball, but he must have a much shorter leash (which I’m sure he does) and much better discretion. If you’re a player like Melvin that is often left alone at the 3-point line because, A) you struggle to shoot them in the first place, or B) you’re left open because the defense is playing to the other two or three shooters on the court, then you must avoid becoming a black hole of 3-point attempts solely because you’re open. You’re largely open because the other team wants you to be open and wants you to take that shot.

Moving the defense

Moving the defense or also known as moving the ball. Creating ball movement usually with passing but also with dribble penetration causes the defense to shift, rotate, and sometimes switch. This creates openings and is a part of not taking a quick shot—you can’t get the defense to shift if you’re not patient enough to pass up the quick shot.

The ball not only needs to be rotated from side to side but inside and out. The guards must trust the bigs enough to dump the ball inside and know that if the post doesn’t have a good shot he can kick it back outside. No different than moving the ball around the perimeter but it often forces a defensive guard on the perimeter to at least look into the paint and potentially lose sight of his man and creating an opening for the offense.

The same is true for ball reversals and not limiting yourself to one side of the court. The whole point to getting a good shot is to not only make the defense work by defending for longer than five to 10 seconds but also to have to defend the whole court.

Earlier in this season, ISU has struggled with some players, at times, becoming speed bumps in the offense. Standing and holding the ball doesn’t continue the defense’s shift and doesn’t make them work. While the ball must be swung quickly at times, each player also must be patient with the ball within the offense to let plays develop and let players free themselves for shots—many times while working of screens. This is obviously subjective and obviously a fine line.

Statistically speaking

There are a few stats that can help with showing a player’s shot selection that I like to use. Granted, it all relies on the fact that players make the easiest shots and miss the most difficult shots, which is not always true. For instance, against Missouri, Anthony Booker missed a dunk and Christopherson made a 65 foot heave in the span of two minutes.

We spoke of effective field goal percentage above so we can start with that (all of these numbers are for the entire season and include Iowa State’s players that have played in at least ten games).

For a frame of reference, of players that have appeared in at least 12 games in the Big 12, 12 are shooting above 60 percent and 53 are shooting better than 50 percent. That puts Allen and Ejim pretty low on the totem pole.

When you look at the Big 12 players that average seven or more points per game, Chris Allen has the ninth worst eFG% and Melvin Ejim has the 15thworst. Perhaps it isn’t a huge surprise that Allen and Ejim are toward the bottom because of the perception of their shot selection and Ejim’s struggles to make jumpers.

The primary reason for Babb being that low is because such a high volume of his shots come from outside the arc and he has been on a cold streak for the past handful of games.

Having Gibson and White toward the top is expected with the number of close range shots they take and Anthony Booker is similar but you must also include that he has been on fire from 3-point range since the start of conference play to help his numbers out. Having Tyrus McGee at 62 percent is quite impressive for a guard that shoots the number of 3’s that he does.

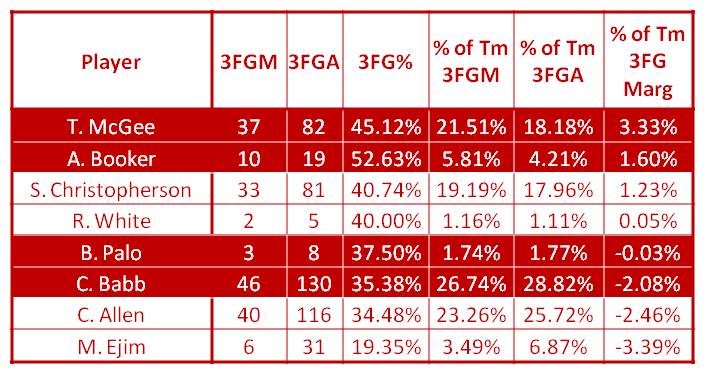

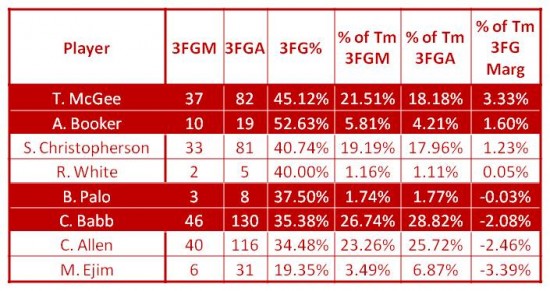

Another stat I like to use is to compare a player’s percentage of the team’s made 3-pointers to their percentage of the team’s attempted 3-pointers.

The theory is that if a player makes a higher percentage of the team’s 3-pointers than they attempt then they are taking and making good shots. Of course ciphering out which player’s are shooting well because they are great shooters and which ones are shooting well because they have a great shot selection can be difficult.

Is it a coincidence that of the four “shooters” (McGee, Christopherson, Babb, and Allen) the two that are making the highest percentage of their 3-pointers have 34 and 48 fewer attempts than the other two?

I will say that by the eye test, Chris Babb has pretty good discretion with when his shot selection. Some of his threes may be contested but there are coming off a screen with his feet set. Chris Allen is probably the one of the four that isn’t as highly regarded as a pure shooter and he takes more threes that are contested off the bounce than the others.

Anthony Booker is shooting 59 percent from the 3-point line this season largely because every shot he has taken has been wide open. I think we would all agree that Christopherson, McGee, Allen, and Babb are better 3-point shooters even though their shooting percentages are lower than Booker’s.

Which leads to this question: in the vacuum of a single possession, would you rather have Christopherson/McGee/Babb/Allen take a mildly contested 3-pointer or have Anthony Booker take a wide open three? Would you rather have Chris Babb take a pull-up jump shot or have Scott Christopherson fire off a runner in the lane?

Keep in mind that all of this that has been discussed so far has yet to include offensive adaptations to adjust for how they are being played by the defense.

An Iowa State Theory

Chris Allen, Chris Babb, Scott Christopherson, and Tyrus McGee are all good to great shooters and have proven that over the course of their careers. My theory that plays a tiny role into the shot selection of ISU and specifically those four players is this; all of them are used to having each and every 3-pointer they take being heavily contested by the defense. They are used to shooting quickly and through small windows of opportunity. They’ve had to in order to get shots off as their careers have gone along.

But, when you put two, three, or sometimes even all four of them on the court at the same time they should be working a little differently. Why? Because it simply is not possible for a defense to guard three shooters that closely at all times. If they do then driving lanes wider than the South Duff flood plain would open up and every possession would be a dunk or a layup.

Each individual’s shot selection must be adapted. Sure, on previous teams with different components each may have been one of two shooters or the shooter and had to fire up shots through the smallest of windows. But this year’s squad is not like that. One or two extra passes following what would have been an open shot on their former teams will now yield a wide open shot for someone else in many cases.

Make sense? Agree?

The Final Word

Outscoring the opponent is always the goal and the way to do that is to maximize your team’s good shots while limiting the good shots of the opponent. A simple thought that seems to get skipped over. If a team is to score a lot of points that will be done by having a variety of scoring threats and varying attacking methods to get good easy looks.

That is the key. None of this was meant to single out a guy to say that he should or shouldn’t be shooting because in the end players play the best when they play freely on the court and not like robots trying to calculate the percentages prior to taking a shot. Discretion needs to be used and everyone must play smart and make good decisions in order to get the best shot for the team on each possession.

A missed long jumper by Royce White or Melvin Ejim is acceptable…in small doses. That’s where the “feel” part of a “good shot” comes into play. I wouldn’t think twice about Chris Babb taking uncontested 3-pointers on three consecutive possessions, even if they were all misses. But for guys that aren’t as adept shooters behind the arc, one is probably the limit in that short of a span.

When you boil it down, it has been Chris Allen and Melvin Ejim that have drawn the most ire from critical Cyclone fans. Allen on occasion gets a shot up a little quicker than you’d like for a guy playing point guard—but he’s always played the off guard and is used to looking to score before initiate. For him to take his game and this team to the next level, he must initiate the offense and create before looking to score on most possessions. Allen using his ability to get to the rim to score and create instead of settling for jumpers could go a long way with the offensive success for the team.

It would likely also get him to the free throw line more. Currently, White has attempted 127 of Iowa State’s 470 free throws this season. Chris Allen is next at 70 followed by Ejim at 58 and Palo at 55 (even without playing since the Texas game).

Melvin looking to score on the offensive end isn’t a problem it is his settling for jump shots that needs to be avoided. The good news is that he seemed to turn the corner in that regard at Lubbock on Saturday.

“Feel”, avoiding quick shots, getting the defense to work, and playing the percentages are all factors into what makes a “good shot.” Much of the evaluation of shots as being good or bad is subjective but the results from taking good shots is not. Sometimes a bounce of the ball makes the final decision. But usually the judgment of a shot being “good” is known prior to whether the shot is made or missed.