Dear Fanatics,

Dr Greenwald here checking in about a fairly common injury affecting athletes, one that can be a ‘real bugger’ and put someone out of commission for quite some time.

It’s the dreaded ‘Hamstring Pull’. It’s something that fans hear about quite frequently so let’s learn something about it.

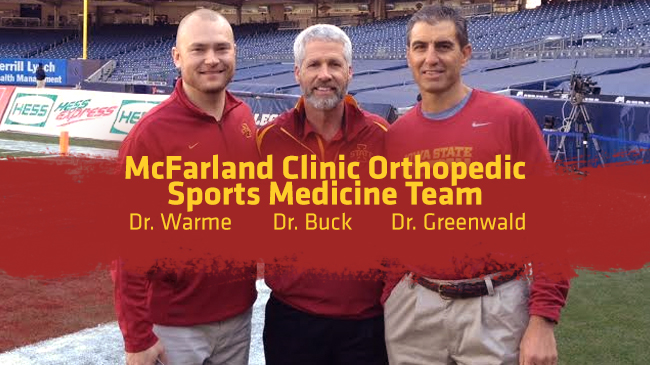

The origin of the word hamstring comes from the old English hamm, meaning thigh, while String refers to the look and feel of the tendons just above the back of the knee. The muscles involved in the hamstring group are the posterior muscles of the thigh, including the semimembranosus, the semitendinosus, and the biceps femoris muscles. They attach at the ischium (the pelvic bone that one sits upon) and move down the thigh and then cross the knee joint.

Functionally, the tendons connect the muscle tissue to bones, and with their location at the back of the thigh, they flex the knee joint and also move the femur (thigh bone) backward. Although the tendons are sometimes involved in injuries, most often it’s the muscle tissue that’s injured–either in mid-substance or at the connection to the tendon.

Most people don’t overuse their hamstrings during daily life, but athletes find these muscle are extremely important in power activities such as running and jumping. Thus, sedentary individuals can get by with quite weak hamstrings, whereas athletes, especially athletes that rely upon speed, absolutely depend on healthy, well-conditioned hamstrings. And late in the season, when one is worn down from week after week of physical demand and abuse, the risk of injury increases.

Hamstring injuries can be caused by rapid acceleration activities, such as a rapid start or when "kicking it into higher gear." These injuries are common in sports such as soccer, football, and track, and range from a minor strain (called Grade 1) to a major rupture (Grade 3). Somewhere in between these are Grade 2 tears – partial ruptures.

These injuries typically occur with sudden lunging, running, or jumping. The sudden contraction pulls on the tissues of the hamstring muscle, hence a pulled hamstring. Oftentimes, a "pop" is heard or felt by the athlete, accompanied by pain. This is usually experienced immediately and frequently the athlete is unable to continue (and sometimes cannot even stand, requiring assistance off the field or track).

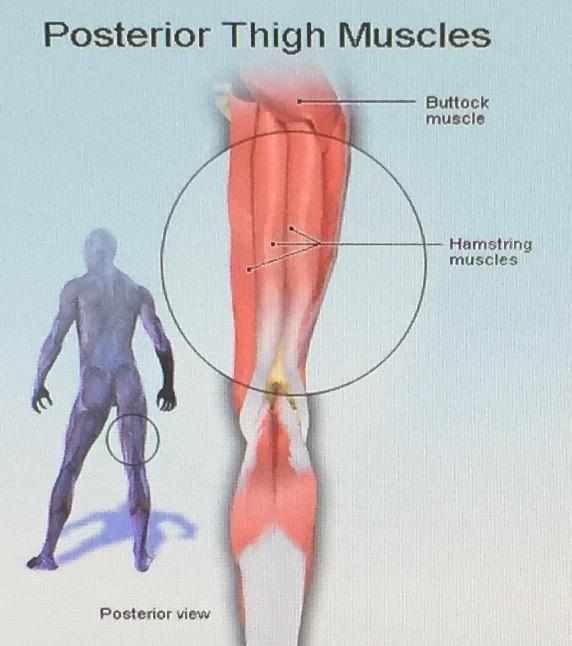

Physical examination reveals spasm, tightness, and tenderness. With more severe injury, swelling and (a few days later) a bruised appearance will follow, as the injured muscle bleeds into the surrounding tissue. In some cases, a palpable defect will be present in the muscle. Use of the muscle is painful and weak. MRI can occasionally be used to further evaluate the injury, helping to grade the injury.

MRI of Grade 2 strain (arrow shows muscle injury)

The goal of treatment is to restore muscle function and prevent scar formation. Initially, treatment consists of rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). Rest is the avoidance of vigorous activities and sometimes includes brief immobilization. In severe cases, crutches or splinting may be necessary. Ice, compression, and elevation all assist in controlling pain and swelling.

As soon as the athlete is able, depending upon comfort, it is important to begin a program of stretching and range-of-motion exercises. Prolonged immobilization and inactivity results in atrophy (muscle shrinkage) and fibrosis (scar tissue), both of which can limit healthy muscle function. Atrophy and fibrosis are best reduced by a monitored program of motion and stretching implemented early in the rehabilitation process. Exercise in water can be especially helpful in getting the recovery process started. As the athlete improves, it is imperative to follow a gradual return to sports activity as re-injury is to be avoided, since this not only prolongs recovery, but can also increase the risk of more muscle damage.

Grade 1 strains tend to be mild in that they tend to heal fully with only minor aggravation to the injured, simply taking some time to heal, followed by rehabilitation which involves stretching and strengthening and return to functional activity.

(Shout out : The ISU ATCs are the ‘best in the Big 12’ and do a super job of getting our athletes back as efficiently and safely as possible.)

Grade 2 strains can be treated similarly, but the healing process takes longer, as does the rehab, with a fairly high incidence of re-injury (re-‘tweaking’) upon return to sports. With grade 2 strains, we sometimes will inject Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) – the body’s natural healing factors (which Dr. Buck wrote about last week) – into the injured tissue, trying to stimulate a better healing response.

Grade 3 injuries can be quite severe and debilitating, and can even require surgical treatment. This is especially the case when the tendon is completely pulled off the pelvic bone. My partners (Dr. Buck and Dr. Warme) and I have done these extensive surgeries, reattaching the tendon to the ischium. This helps restore normal anatomy, but the functional recovery process for the patient is long and arduous, often taking months for full recovery.

As you can see, "hamstring pulls" can really slow down an athlete. Let’s hope the Cyclone athletes can avoid these in the future.

Until next time, Go Cyclones!

Dr. Thomas Greenwald.