CLEVELAND, Ohio – A football stadium almost 700 miles from Cleveland, amid the central Iowa plains, bears a direct, and tragic, connection to Cleveland: Jack Trice, a native Northeast Ohioan, died during a college football game 100 years ago. Eventually the stadium at Iowa State University would be named after Trice.

It remains the only Division I stadium to be named after a Black man.

Trice’s story, how he got to Iowa State, and his brief career have strong ties to Northeast Ohio.

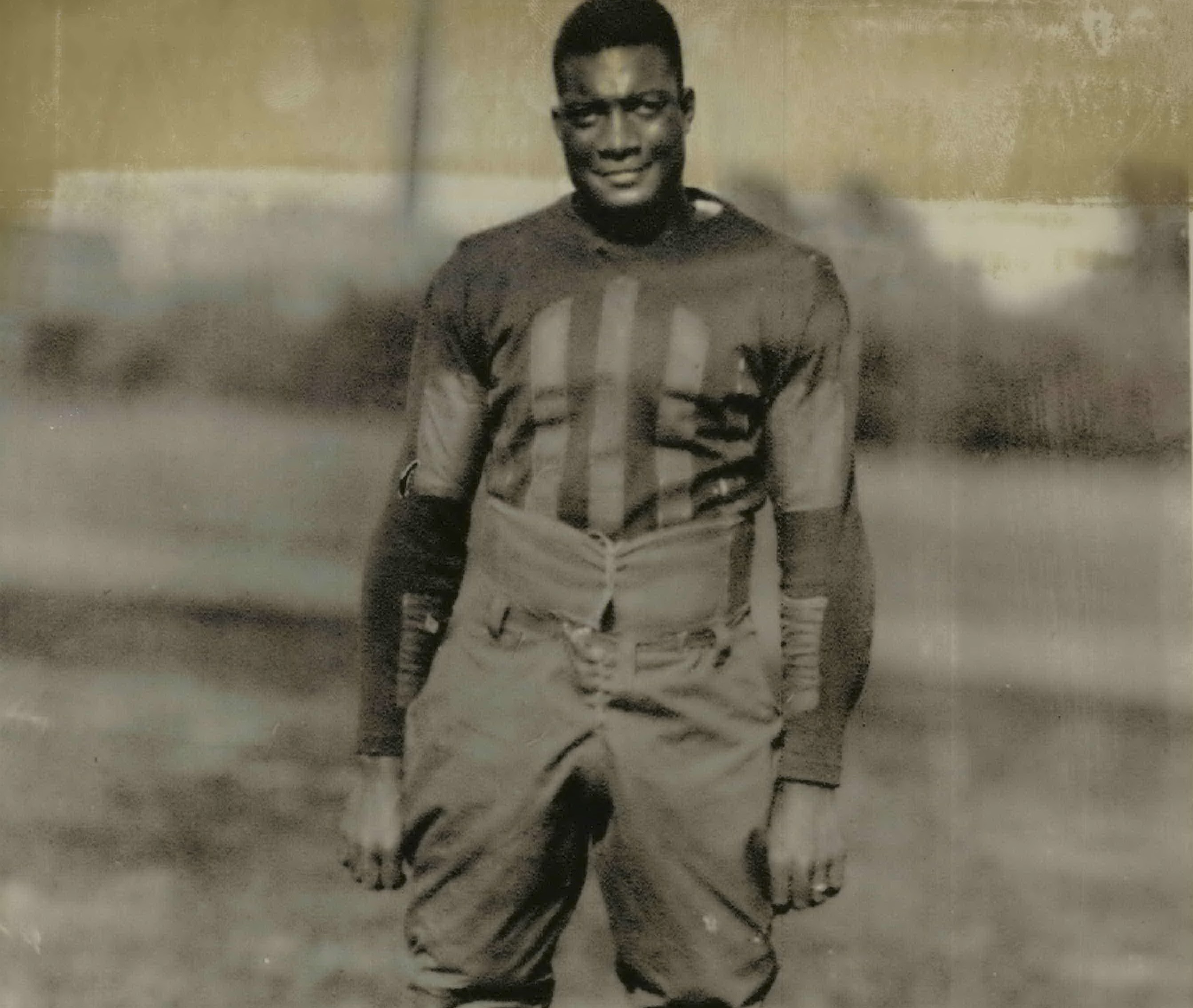

Born in 1902 in Hiram, Trice was the son of a Buffalo Soldier, the 19th century Black Cavalry units. After his father died when he was young, his mother sent him to Cleveland, where he played football at East Tech High School.

On Nov. 18, 1921, East Tech rolled over Central at Shaw Field, 88-0. Trice merited a mention in The Plain Dealer: “Jack Trice, the big Tech tackle, started the game at fullback and hit the line (with) several resounding wallops, going through for eight yards and the second touchdown.”

Trice found the Iowa school through his high school coach, Sam Willaman, who took over as the then-Iowa State College coach and brought with him East Tech stars.

For school expenses, Trice worked construction, and on a hot summer day met a girl named Cora Mae. They fell in love and in 1922, after a strong freshman year on the football field, he came back to Ohio to marry his sweetheart.

Trice majored in animal husbandry, reportedly hoping to teach farming techniques to Southern Black farmers. His wife studied home economics.

Growing up on a farm, Trice was country strong, and by the time he was a college sophomore he weighed more than 210 pounds.

He did well off and on the field. He earned good grades and ran track. He won a Missouri Valley Conference meet in shot put and discus. Both he and Cora Mae worked part time.

He also was well-liked. Johnny Behm, who was teammates with Trice at East Tech and Iowa State, told The Plain Dealer’s Hal Lebovitz in 1979 they were best pals.

“Jack Trice was one helluva nice guy,” Behm said. “No better tackle ever played high school ball in Cleveland. There is no question in my mind he would have become an All-American.”

Behm also liked to sit next to Trice on train rides because porters – then one of the few steady jobs for Blacks - would give extra portions to both young men.

The game

Iowa State was scheduled to travel to Minnesota early in the season. It was his second collegiate varsity game. The first one, which he played some, had been the week prior against Simpson, a private Methodist college about 60 miles south of Ames, and not much of a test.

The night before the Minnesota game was a solitary one for Trice. Because of the racial mores of the day, he was barred from eating in the Curtis Hotel, where the rest of the team was staying, and isolated in the Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House.

On Oct. 5, 1923, he spent the night jotting notes that amounted to part journal, part self-motivation on hotel stationery:

“My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family and self is at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will.

“My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about the field. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part. Fight low, with your eyes open and toward the play. Watch out for crossbucks and reverse end runs. Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good.”

Not long after, those words would help immortalize Trice.

The next day, with temperatures reaching into the low 60s, Iowa State took the field. In the first half, Trice hurt his shoulder but stayed in the game against the bigger Minnesota team.

In the third quarter, Minnesota led, 14-10.

Trice lined up, and with the snap came a crossbuck, with blockers running diagonally. Trice forged into the offensive line. Three Minnesota players converged on him. Many accounts of the play use the word “trampled.”

After the play, Trice wanted to stay in but couldn’t get up. Behm couldn’t say whether the play was racially motived or whether it was just an overwhelming triple team that devastated his teammate, but either way: Trice was injured seriously.

Other reports said it definitely was racially motivated, that players viciously stomped Trice, and the Ku Klux Klan reportedly had members at the game.

As he was helped off the field, Minnesota fans reportedly shouted: “We’re sorry, Ames, we’re sorry.”

After being released from the hospital in Minnesota, Trice rode with his teammates back to Ames, laying on a straw mattress on the train. The 200-mile trip must have been agony for Trice. He had trouble breathing on the journey.

In Ames, he was taken to a hospital. Doctors said surgery couldn’t help him. He had suffered intestinal injuries, internal bleeding and a broken shoulder blade or collarbone.

Two days after the game, Trice died.

Trice’s legacy is clearly one of unfulfilled potential.

“I think you categorize him from the standpoint of the letter found in his suit,” said Jeff Johnson, chief executive of the Iowa State University Alumni Association. “Basically, it was not written for anyone; it was just his thoughts.”

Jack Trice, who played high school football in Cleveland, died 100 years ago.

More on Minnesota

A little more than a decade later, the University of Minnesota football team again would be connected to racial brutality on the gridiron: The University of Iowa, Iowa State’s out-of-conference archrival 100 miles away to the east, has its own sullied history with the school up north.

In a 1934 game, Minnesota players pummeled Iowa’s Ozzie Simmons, a Black player.

A year later, Iowa fans had not forgotten the treatment of Simmons.

Minnesota Gov. Floyd B. Olson telegrammed Iowa Gov. Clyde Herring the morning of the game, proffering a wager of a prize hog.

Minnesota won. The tension was lightened.

Over time, the prize became a bronzed pig – Floyd of Rosedale – and to this day remains the traveling trophy between the two Big Ten schools.

Final footnote: Floyd, the pig, died of cholera in 1936 and was buried six miles from Iowa, roughly halfway between the schools in a gesture of equity. Floyd the governor died about a month later from cancer.

Iowa holds a slight edge in the series for the trophy, a rivalry rooted in racism on the field, and has won the last eight games between the schools.

The aftermath

In Ames, 4,000 attended Trice’s services. His casket was covered in Iowa State’s cardinal and gold colors. His body was transported to Hiram’s Fairview Cemetery.

The rest of the season, the team wore black armbands.

Iowa State lost to Minnesota that day, 20-17. The Cyclones finished the year 4-3-1. Despite Trice’s death they played a week later at Missouri, winning, 2-0.

In 1925, a bronze plate was placed in the Iowa State gymnasium to remember the fallen player.

In 1957, the faded, dirty plaque was found behind a staircase. A student eventually researched and wrote a story about it, and Trice’s name rose to the surface.

In the 1970s, the idea surfaced that the football stadium should be named after him. Finally, in 1997, it became official: Cyclone Stadium would be known as Jack Trice Stadium.

Johnson credits efforts primarily from the student body over more than 20 years for Trice’s recognition.

“This is an individual who gave everything for his desire to get an education through athletics. That story and legacy needed to be told and upheld by the university,” Johnson said.

“As all of us know,” he added, “this could have been an easy project to make money off of for naming rights, but the story and the opportunity was so compelling that this was the right thing to do. We didn’t do it to be the only one, but here we are today standing with the only stadium in Division I in this country named for a Black student-athlete.”

Cora Mae, from Ravenna, left campus. She never returned. She remarried.

Tragically, the Salem, Ohio-born Willaman, Trice’s well-respected football coach who brought the young player from East Tech to Iowa State, died after intestinal surgery in Cleveland in 1935. He was 45.

Iowa State would play Minnesota to a tie a year later, in 1924. They would not play again until 1989 and have met a total of only five times since Trice was killed.

Trice is immortalized in three places at the Ames campus.

The stadium bears his name. A statue stands in the middle of campus, north of the university’s administration building. And the third is a recent sculpture that was installed outside of the stadium. It’s called “Breaking Barriers.”

“It is a tribute to Jack Trice - not a statue, but an art installation,” Johnson said. “It is an image of Jack’s body in his suit running through this stone, and basically breaking the barrier of the stone and coming out the other side. But the stone is actually cracked in two, but you can see his body formation.”

Christopher Bennett created the eight-foot statue in 1988. North Carolina-based artist Ivan Toth Depeña sculpted “Breaking Barriers,” which was installed last year.

In a 2020 story, The Des Moines Register quoted Cleveland St. Joseph High School graduate Desmond Howard, a former Heisman Trophy winner at Michigan, about Trice.

“We like to hype up Rudy, and Rudy didn’t do a damn thing compared to Jack Trice, but we make movies about Rudy,” Howard said about Daniel “Rudy” Ruettiger, the glorified walk-on Notre Dame football player in the 1960s. Hollywood took his story to the

big screen 30 years ago.

“That’s how wrong it is.”