Sep 2, 2022; Boulder, Colorado, USA; General view of a PAC 12 time out clock during the first half between the TCU Horned Frogs against the Colorado Buffaloes at Folsom Field. Mandatory Credit: Ron Chenoy-USA TODAY Sports

By Connor Ferguson, with data provided by Sports Data Analyst Michael Egle

The diehards that tune into every press conference have heard coach Matt Campbell emphasize the importance of having a strong start to a football game.

While that might have fallen into the coach-speak category in previous seasons, it now carries a whole new meaning and level of importance.

“We always used to say — and I still chuckle — you want to get out to an early lead, well everybody does,” Campbell said. “It’s more important now.”

I brought in the smartest analytics friend I’ve got in Sports Data Analyst Michael Egle to help explain why. Dig in and enjoy.

***

Go back to week 1. Iowa State played UNI and recorded a win while running just 45 plays from scrimmage. It was the lowest number of plays ran in an Iowa State win since 1961.

It was also the first game the Cyclones had played that featured the NCAA’s new timing rules, which nixed the temporary clock stoppages given to offenses after first downs or plays that ended out of bounds, up until the final two minutes of each half.

“This rule change is a small step intended to reduce the overall game time and will give us some time to review the impact of the change,” Kirby Smart, the co-chair of the NCAA Football Rules Committee for Division I and Division II football and Georgia coach, said in the original release that announced the changes.

The rules were put in place to limit the amount of plays collegiate athletes are on the field for, and so far it has.

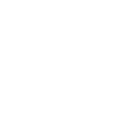

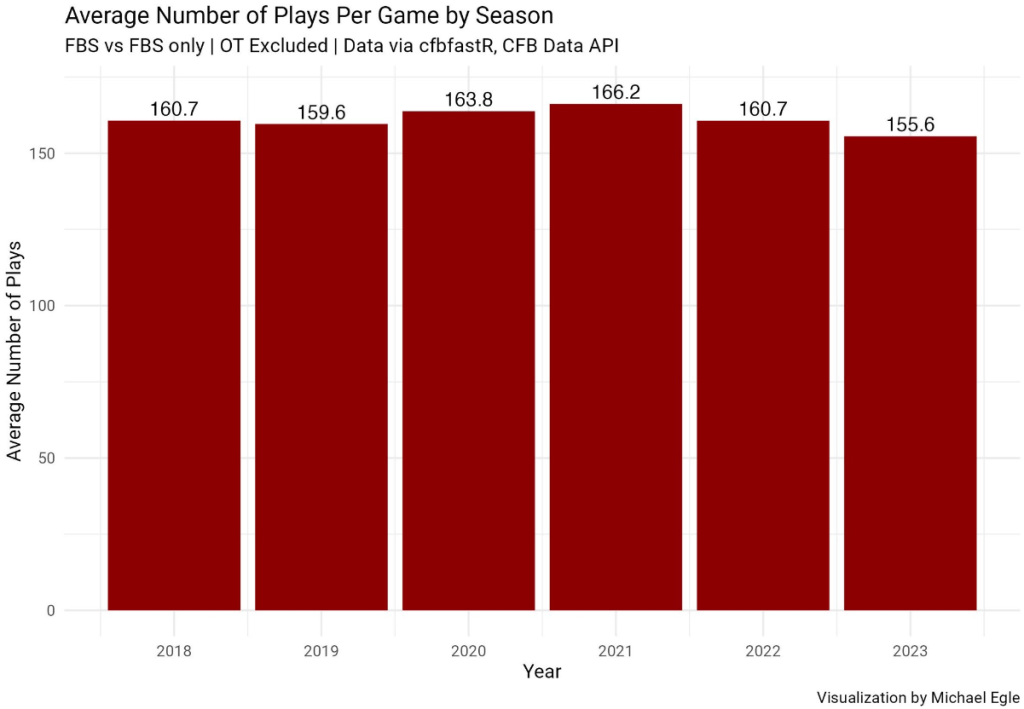

College football teams are averaging five fewer plays than they did a year ago.

This is being framed as a measure to increase player safety, but like with many modern NCAA rule changes, the move has been accompanied with unintended consequences.

So I started to pay closer attention to these new timing rules. The games felt shorter to me, and to a lot of those watching at home, the commercials felt even longer.

“I think it’s a fascinating story to look at,” Campbell said. “It has felt like the games are just different.”

The more I watched, the more I felt the same.

There are fewer possessions — fewer drives — in the average game, which takes away scoring opportunities, obviously.

Total possessions in games in which FBS teams face each other are also down by nearly 2.0 possessions per game, nationally.

While fewer possessions and fewer plays were likely expected, there’s some hidden time — that’s a nod to my co-hosts of Football and Random Things, Jeff Woody and Colin Newell — two guys I’ve talked with ad nauseam about what is going on.

As noted earlier, at the end of a play that resulted in a first down or a player going out of bounds, the clock continues to run until the ball is spotted, which, again, is different from years past. The play clock continues to start once the ball is set, but the seconds in between the end of the last play and the physical spotting of the football vanish into the ether.

There’s time running off of the clock, and it becomes more important when down by multiple possessions in the second half of games, especially in the third quarter.

“We’ve talked about the third quarter being the most critical quarter in college football right now, because of the new timing rules, the ability — whether you’re up or down — to win the third quarter,” Campbell said. “It feels like most teams that have the ability to do that sustain success.”

His team found itself in that spot Saturday, trailing No. 16 Kansas 21-3 before attempting to mount a comeback.

During the game, Iowa State held the football with eight seconds remaining in the third quarter. It went on a 12-play drive, but when the first play is omitted, the 11 plays that followed took eight minutes and one second off of the game clock.

What is happening here is the opportunities for a team to play its way back into a game are being drastically limited.

“I think it can make it a real challenge, especially with a young football team,” Campbell said. “I think what’s even more important, is that when we do get behind, (we have) the precision of play in the second half.”

Teams playing with that lead can sit back and watch the game clock run. If the offense of a team trailing makes a substitution, you’re going to bet that the defense will, too, in the Mike Gundy-esque effort to squeeze every second of milk out of the clock’s udder.

Iowa State has talked about that distinct advantage within its walls, too.

“Playing with a lead at times is something that we’ve talked about internally — any time that you’re not going to get more snaps or more possessions in a game,” Campbell said. “I think one of those things the studies have shown is that you’re down two possessions per game — that’s staggering.”

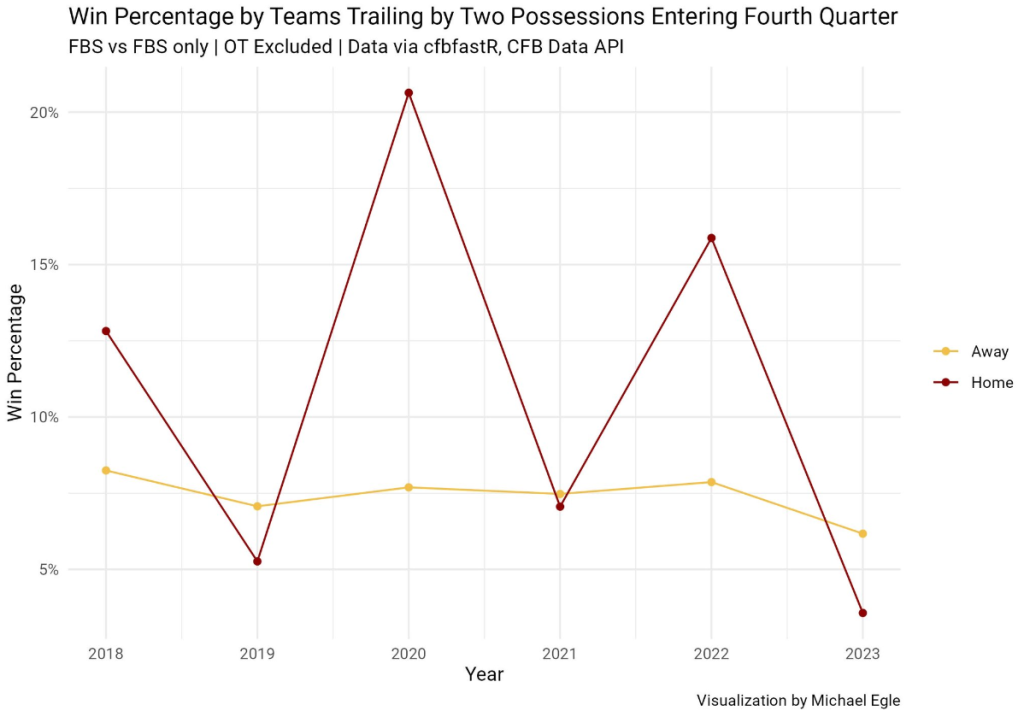

Comparing teams that enter the third quarter trailing by two possessions and their success rates in pulling off comebacks shows drastic changes, as well.

While home field advantage and momentum certainly can help swing a resurgence, it’s hit the lowest success rate in five years. Michael and I both theorize that momentum swings and rivalries between uneven programs are the reason for how much the home team’s success rate bounced around.

However, road teams have been rather consistent in recent years, and their success rate comes in at a five-year low, as well.

It’s made comebacks harder to accomplish, playing with the lead that much more advantageous, and third quarters increase in importance.

Cyclone fans saw that firsthand on Saturday, and it’s become a new wrinkle to tackle for a staff with a rookie play-caller and young, sprouting team.

“There’s certainly validity that it’s changed a bit of the mindset of the football game,” Campbell said.

And it has.