For as long as I can remember, it has been my dream to help people tell their stories. This is why I went to journalism school. And when I got to journalism school, I realized my dream was even more specific: I wanted to write stories about people through the lens of sports.

But then the economy crashed. I got spooked and, suddenly I found myself in law school despite never having dreamt of being a lawyer.

As it turns out, though, dreams are persistent. And as my career as a lawyer progressed, I couldn’t shake this tugging feeling that I needed to find a way to get back to telling stories.

So, I reached out to the only person I could think of who might be able to help me. You may have heard of him. It was my old friend from journalism school, Chris Williams.

Chris and I made plans to get together numerous times over the span of several years but as often happens in life, things kept coming up. But last summer the tug became unbearable — like a constant ringing in my ears. So I reached out to Chris one last time. And by some incredible streak of luck, life didn’t interfere. We finally had our chat.

Now, thanks to Chris and our chat, I have a platform at Cyclone Fanatic to tell stories. But I also got more. Chris went from an old friend to a best friend. I gained a whole crew of new friends. And the decade-long tug is finally gone.

I detoured from my dream, yes. But like I said, dreams are persistent, and I can’t help but feel like things worked out just as they were supposed to.

So, all of that to lead me here — to introduce a new way I want to use the platform Chris has given me to tell stories about people through the lens of sports: Fanatics, I want to tell stories about you.

I want to tell your story about the chance encounter at a tailgate that led to a lifelong friendship or even a marriage. I want to share the random act of kindness from a fellow Cyclone that made your day. I want to hear about your neighbor who is the most diehard Cyclone fan you’ve ever met. I want to help you share how being an Iowa State fan has shaped or even changed your life.

If you have a story to tell, reach out to me (@StephCopley on Twitter or [email protected]), and let’s tell it.

This is the first of what I hope is many such stories I get to tell at Cyclone Fanatic. This is the story of Joyce Sharp and her love affair with Iowa State football.

. . .

I first “met” Joyce Sharp as many of us meet each other these days — on Twitter. She tweeted well wishes at me after listening to the episode of the Title IX Podcast in which I admitted being worried about my mom’s upcoming oncology appointment. Joyce’s words were kind, a descriptor that is increasingly rare when it comes to social media these days.

But not for Joyce. In fact, Joyce regularly tweets encouragement and praise at the entire Cyclone Fanatic staff. And it was one of these supportive tweets that prompted Chris to message me and say, “Hey, you should really write about Joyce.”

So Joyce and I set up a phone call and as it turns out, Joyce is just as sweet on the phone as she is on Twitter.

But she’s spunky too.

At 70 years old, she had me in tears from laughing so hard, and I found myself thinking several times during our hour-long conversation that she’d fit in great with my group of 30-something girlfriends.

For example, Joyce told me about a term she coined years ago when Fred Hoiberg was at Ames High.

“Well, I had such a — I call them ‘mom crushes’—on Fred Hoiberg when he was playing in high school. When I first started going to Iowa State football games and looking at the young men on the field, they were my age. But then at a certain point, you think, ‘I really can’t have a crush on this guy because I’m way too old.’ And then it turns into, ‘That could be my son.’ And now they could be my grandsons! So that’s what we call it—we call them ‘mom crushes.’” (Ladies, let’s make “mom crush” happen.)

This spunk of Joyce’s dates back to her childhood—as does her passion for sports.

“The first time I started to enjoy sports was as a way to bond with my grandfather and my dad. They’d tell me who was playing and what each play was. Then when I was 11 years old, my family went to Chicago and we stayed with my grandfather’s brothers in the suburbs. The men decided they were going to go to a Cubs’ game and I was like, ‘Well, wait, I’m going.’ They told me they thought it’d be a thing for the guys, but I said, ‘Too bad. I really want to go.’”

They listened, and Joyce got to spend her 11th birthday at Wrigley Field.

But it wasn’t just baseball that Joyce loved. It was football too. Joyce was born into a “sports family” and grew up in small towns in central and southwest Iowa. As any small town Iowan knows, that meant Friday nights in the fall were spent under the lights at the high school football stadium.

“Every Friday night everyone went to the football game — it was a whole town thing.”

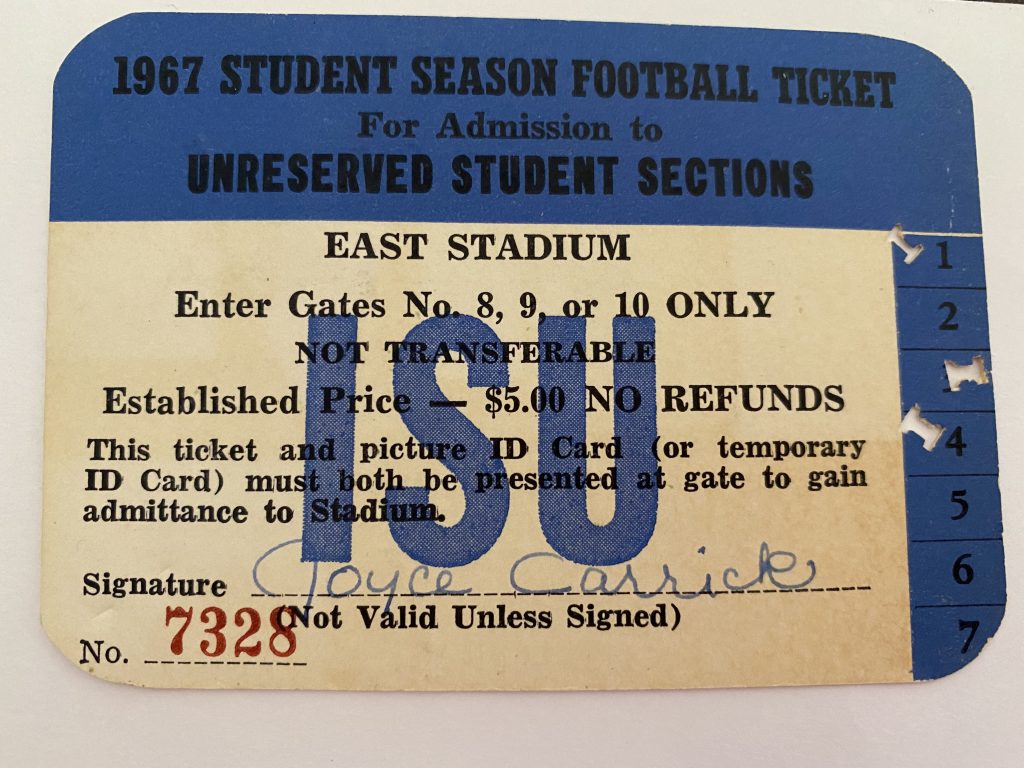

So when Joyce became at student at Iowa State in the fall of 1967, one of her first orders of business was getting her football season ticket.

“You got it punched, like a piece of paper, and it had your name on it. It cost five dollars. That was at Clyde Williams Field.”

That five-dollar ticket has since become priceless to Joyce, who still has it to this day.

Part of its immeasurable value is the decades of family tradition that student season ticket set into motion.

“Since my family loved football so much and since I was the first one to leave the house, my parents started coming up to games.”

Before long, her parents purchased four season tickets—one for each of them, one for Joyce’s brother and one for Joyce. And not long after that, four-season tickets turned into eight.

“When they were building the new (Jack Trice) stadium, my dad was really curious to know how it was all laid out. He decided he was going to go get eight tickets that year, for him and my mom, me and my husband, my brother and his wife, and an aunt and uncle. We’d always done tailgating together. So in the summer of ’75, he drove to Ames and walked into the ticket office and said he wanted to go into the stadium to walk around to see where he wanted to sit. And they let him. He went in and walked around and decided where he wanted our seats to be.”

Joyce’s dad handpicked eight seats — two rows of four — in section 5.

“We were in section 5 from the very first game at that stadium until my husband and I gave up our tickets in ’89 or ’90 — about the time our kids started having all sorts of things on the weekends.”

By then, Joyce’s family was well aware of her spunk, and they planned accordingly.

“The men, of course, sat in the front row, and the women sat in the back, but they made my dad and me take the aisle seats because we were the loudest and jumped up and down. They knew that was the safest place for us to be.”

These eight seats gave Joyce what she described as “wonderful years” of memories with family — not to mention football.

“I got to see Earl Bruce, Donnie Duncan, and the first time we beat Iowa in that stadium. And probably one of the best football days of my life — the day we beat Nebraska and Luther Blue started his kickoff return right in front of us. That was just amazing.”

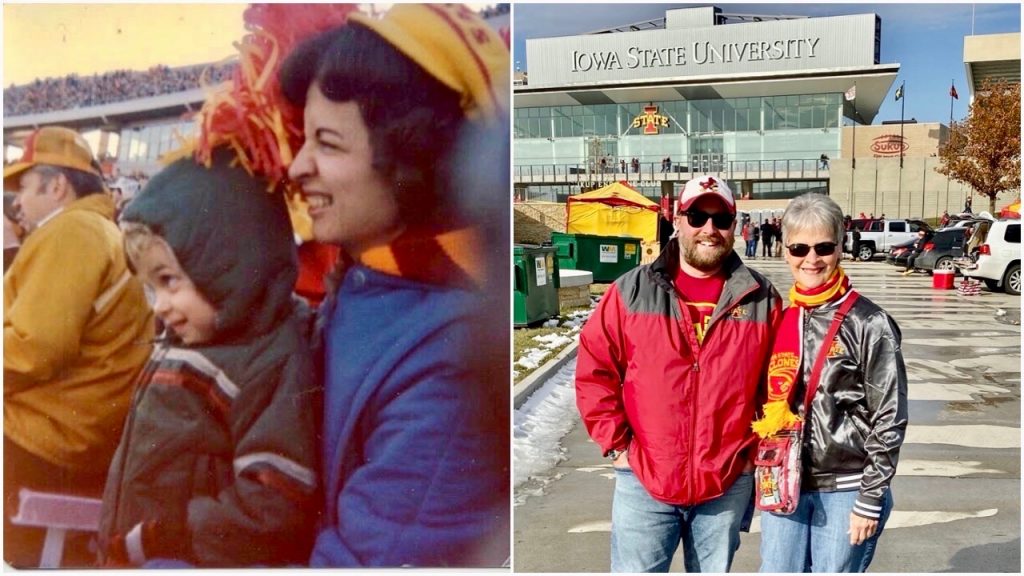

Though Joyce gave up her football season tickets for several years while her sons were growing up, she still made the trip to Jack Trice with them whenever possible. It’s a tradition she and her boys have continued to this day.

During the final home game last year against Texas, Joyce and her son stopped to take a photo together on the way into Jack Trice.

“We asked someone to take our picture on the way in, and it occurred to me that in November of 1979, 40 years earlier, I took that same kid to his very first game. I have a picture of that too, so we put those two pictures together as a side-by-side.”

A few years earlier, in the mid-2000s, Joyce was joined by her oldest son, who hadn’t been to Jack Trice in years.

“He said, ‘Can we walk over to the section where we all sat with grandma and grandpa?’ And of course, I wanted to do that. So we did — we walked over — just to get that feel. My dad liked it there because it was close enough to the field so that when the team was playing in front of you, you really saw and felt everything.

“At the end of the game we went to leave and we stopped at the hillside —the part that is now bowled in. I said, ‘Let’s just sit down for a minute.’ It was a beautiful night and the moon was out and we were winning and the stadium was full. I told my son ‘We have something we’re going to do tonight,’ and we put some of my father’s ashes down. Now it’s bowled in, so he has a permanent good seat.

“I’m one of those people for the first game of the year when the band comes out and starts playing that fight song, I’m in tears. I look at those 60,000 people, most of them wearing red or gold, and I think, ‘My dad would be so excited.’ He would never believe what this looks like now because we went to a lot of games with 30,000 people in the stands. He would just be thrilled.”

Now that Joyce is retired and her sons are grown, she’s a season ticket holder again. She’s only missed one home game since the start of the 2017 season, and that was for her son’s wedding in Portland.

“When they told me the date, the first thing I said was, ‘Wait! I think we have a football game that day.’”

To be fair, Joyce had a similar reaction to her own engagement decades earlier.

“When I planned our wedding, I called Iowa State and said, ‘We are season ticket holders and I need to know the home football schedule this fall.’ He gave it to me and said, ‘Just out of curiosity, what’s coming up?’ I said, ‘I’m getting married, and if I pick the day of a home game I’m not sure my father will be there to walk me down the aisle, and it’d just be too distracting for me too.’”

Like the rest of us, Joyce is nervous about the impact COVID-19 may have on the upcoming season. She knows her age might be a prohibitive risk factor even if fans are allowed into Jack Trice. But her attendance aside, Joyce just wants football and somewhere to channel that spunk.

“Look,” Joyce told me matter-of-factly. “If there is no football season, I’m going to need some serious therapy.”

Me too, Joyce. Me too.