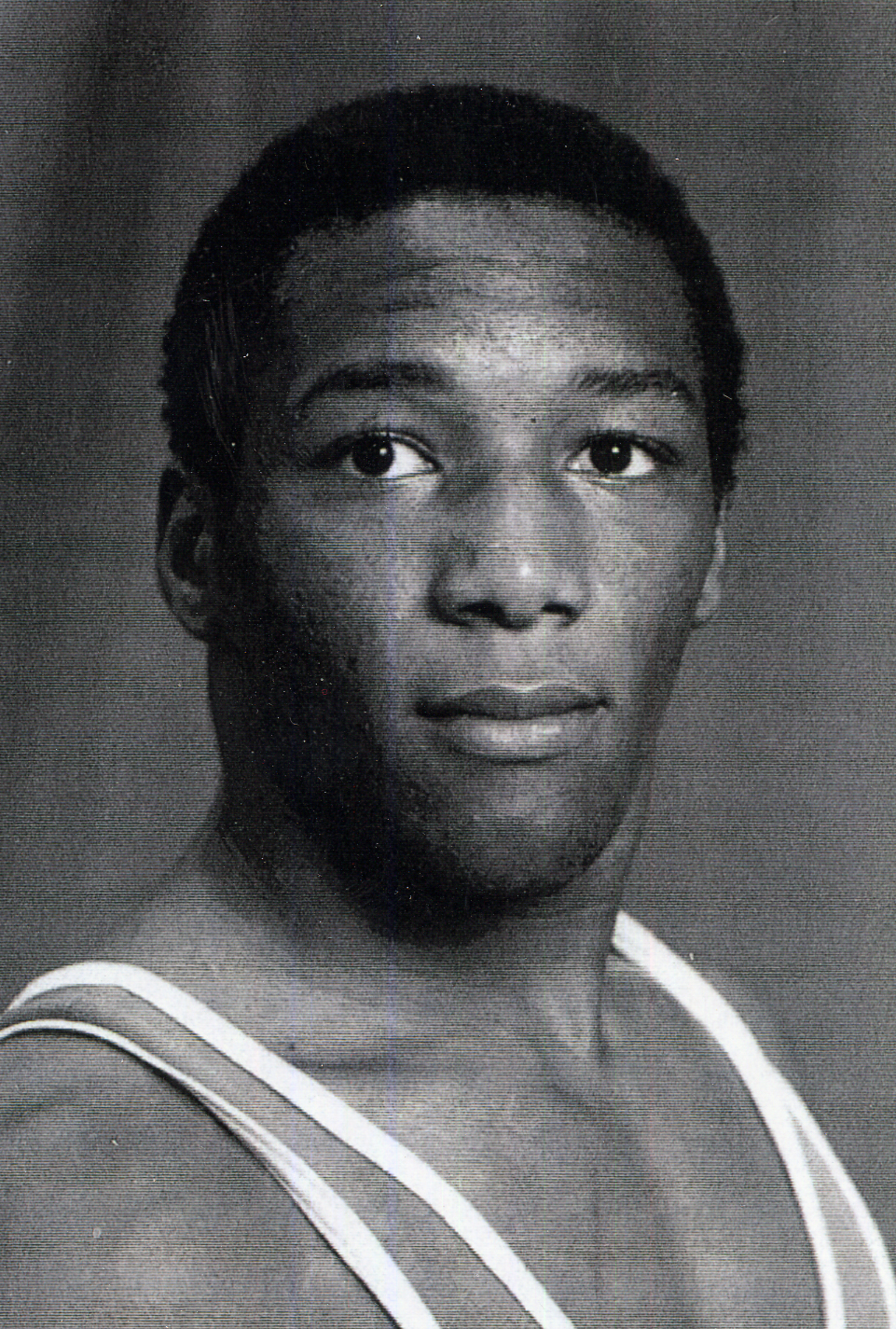

Nate Carr won three straight national titles at Iowa State and is back at his alma mater as an associate director of the Cyclone Regional Training Center. (Photo courtesy Iowa State Athletics Communications)

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article originally ran on Cyclone Fanatic on June 17, 2019. As the sports world comes to halt during the Coronavirus Outbreak, we will be re-releasing one of Rob Gray’s Where Are They Now features every Tuesday and Thursday with some new updated stories sprinkled in between.

AMES — Dan Gable and Chris Campbell.

Those two names and more sold Nate Carr on Iowa wrestling four decades ago. The future Iowa State star fully planned to join the Hawkeyes’ program, where during one last recruiting pitch, the iconic Gable told the prospective recruits he’d flown in that if they committed, it would complete “our dynasty.”

Goosebumps. I’m in, but, wait … what’s that? Mom?

Carr’s mother, Luella — to this day, a portrait of grace and generosity at 91-years-old — had decidedly different ideas that sprang from a fertile subconscious.

“So my mom has a dream and I’m leaning toward Iowa,” said Carr, who won gold in the Goodwill Games, the Pan-American Games and the World Cup, while earning bronze in the 1988 Olympics. “Gable — come on! They’re doing pretty good. He’s doing unbelievable. So I’m leaning there, hard, and my mom has a dream and she says, ‘I think you should go to Iowa State.’ I was like, ‘Wow.’ And of course, I’m young, feeling myself, so I say something like, ‘You know what, mom? I really respect you and it is my decision and I’m going to go to Iowa.’ So then, to make the story short, my mom has another dream. Then I was like, ‘Aw, forget it.’”

The stuff of legends thus merged with the stuff of dreams.

Iowa State would be the site of that powerful union — and Carr would be the alchemist molding the combustible mix into three straight national championships at 150 pounds from 1981-83.

He’d wrestle an Iowa rival in a sauna along the way. He’d beat Olympic and world gold medalist Kenny Monday twice to clutch a crown. He’d meet, Linda, the woman he’s still married to today — and who once stitched together a handmade, unpublished, but prophetic scrapbook for him entitled, “On Your Way to a Third National Title.”

What a journey. What a life. What a legacy — and it continues, via his highly-decorated son David, who seeks to trace and perhaps add a twist and turn or two to his dad’s inspiring Ames-based story.

“Met my wife here,” Nate Carr said. “Met Linda here 39 years ago. So when (son) David gets on the mat (this season), it will have been 40 years since I wrestled. So when I went into the Iowa State Hall of Fame, I said Iowa State has given me family, friends and a future.”

***GENESIS***

Nate Carr’s parents moved to Erie from Mississippi in the late 1940s. His dad, Fletcher Sr., started a church. He also got a job at General Electric and became a foreman and began building a new life, where by dint of iron will and hard work, dreams could take flight.

“That’s where he gave his life to Christ,” said Carr, who’s also a member of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. “Him and my mom. 1949, Thanksgiving Day. They started a family. And I always say this kind of with a little bit of tongue and cheek and sarcasm that when my dad became a minister, he really took Genesis — you know, ‘Be fruitful and multiply’ — literally. So I have 15 other brothers and sisters. So that’s pretty much where it started. My dad, strong guy. I think he boxed a little bit. He was a foreman at General Electric and all of that. Pretty much just the Gospel was really big, because that’s what he did. And they worked. Started a church and my brothers wrestled.”

They wrestled all right.

His oldest brother, Jimmy, broke new ground in the sport by qualifying for the World team at age 16 and the Olympic team at age 17. Another brother, Fletcher, became an all-American wrestler and coach at Kentucky. Five Carrs attained all-American status — an NCAA record.

And it all started, as usual, in a well-kept living room, they would delightedly (but carefully) tear into.

“So this is the sofa,” Carr said, motioning to a spot. “You would try to pick up a sibling and make sure they landed on the pillow cushions. So that was interesting. You had to be careful, right?”

That’s out of respect for mom.

But a young Nate Carr established his own audacious dream: To become the “winningest man in the family.”

That dream came true, too, but Jimmy certainly got his licks in.

“I remember (Jimmy) beating me up pretty good,” Nate said. “Those dudes were rough. He was five years older than me. I’m thinking, ‘Dude, I’m getting you.’ That’s what my mind said. Then of course other brother, Joe, is over there watching, and (I say), ‘I’m gonna take you down.’ He was like, ‘No you’re not.’ I was like, ‘Oh no, I’m taking you down.’ And of course he would talk to my brother Joe, ‘Joe, tell him, I’m not letting him take me down.’ ‘I’m gonna take you down!’ Then I start crying, running after him and then, of course, he would remind me of that all the time. So that’s memorable because I’m thinking, ‘Dude, I’m taking you down,’ but I don’t really realize how good he is.”

By the time Nate realized how good he could be, his brothers tended to agree. Dream big. Work hard. Believe that anything is possible.

So when Jimmy gave then-12-year-old Nate his 1972 Olympics uniform to wear before a big tournament, a funny thing happened.

“I don’t think nothing of it,” Nate said. “I’ve got (14) other brothers and sisters, so to get a jacket, some jeans, shorts, hand-me-downs, is commonplace in the house. Except it’s really nice. It’s got the rings on it. It has USA on it. I have to admit it is pretty decked out. And I went to a tournament, and I kid you not, me wearing that uniform got me to the finals. It scared the other guys. So I have a talk and one of my talks is, ‘Wrestle the man’s body, never his name, his history, his schools,’ which is what people do.”

Nate kept winning. It didn’t matter what he wore. By the time a college choice loomed, he’d eliminated Kentucky and Iowa was the clear leader. But Hall of Fame ISU coach Dr. Harold Nichols entered the picture and cast a large shadow. He even came back to attend the same-day wedding of two of his sister. His parents clearly liked him, too — and then the second dream occurred.

“Spiritually, I think she was just saying, ‘I was steered, I was nudged, I have a sense that this is where you should go,’” Carr said of his mother’s fateful premonition, one of many that rang true. “One time she told me — I was going to a tournament — and she said, ‘You know, dress warm,’ because it was snowing. (She said), ‘I had a dream that you’re gonna get stuck or be out in the cold.’ And I kid you not, going to this tournament, we almost went off a bridge. We didn’t go off, but we were on the edge. We had to get out. It was scary. But anyways, I was warm.”

*** “HE CAN JUMP ROPE, BUT CAN HE WRESTLE?” ***

Coach Nichols populated his wrestling room with stern competitors at every weight. Making the lineup was tough. Keeping a spot was also hard. Carr, as the new guy, stirred up skepticism in some Cyclones.

“First day in the room, I wrestled (NCAA champ) Kelly Ward,” Carr said. “And I come in, I’m jumping rope, and I can hear people whispering, ‘He can jump rope, but can he wrestle?’ And Kelly Ward comes over and says, ‘Nate, you wanna go?’ I was like, ‘It’s a wrestling room. Yeah.’ So we wrestle and I duck him, take him down to his back. He got up again. I duck him and take him down again. And the room pretty much starts saying, ‘Get him, Kelly!’ I mean, the guy’s a national champion. So they’re like, ‘Get him!’ And he finally got me down and, boy, he put it on me. Riding on top, breaking my arms off, and I was a competitive guy, so I just whispered this to him: ‘You know what? Before you leave, I’m gonna get you real good.’ And before he left (wrestling), I got him real good, because he went to (coach) Nebraska.”

Ward eventually served in the U.S. Secret Service. Carr rose as high as No. 4 in the rankings for 150-pounders his freshman season, but the season did not end as planned. Carr would lose by just one point (in a dual meet) to eventual champ, Andy Rein of Wisconsin, but the national meet took an unexpected — and painfully decisive — turn when he matched up with four-time all-American Roger Frizzell of Oklahoma.

“I had beaten him in the Big Eights and wrestling him at nationals,” Carr said. “I’m up 5-1 and I have good balance, so I’m trying to get up and the guy spladles me. That’s when they split your legs and ooh that was bad. So basically I tore my hamstring. Now, I’m still wrestling. Can’t walk but I’m still wrestling back. Made it to OT in one match, and lost because of an unnecessary roughness call.”

Just like that, one dream evaporated. But dreams don’t die. They merely transform.

“I’m walking out with coach Nichols and I said something like this — a true story,” Carr said. “I said, ‘You know what, Nick? I’m gonna win this next year.’ And his response? ‘I know.’

***FROM THE SAUNA TO THE TOP OF THE PODIUM***

Carr already knew he didn’t like star Iowa wrestler Scott Trizzino, who had belittled him during a recruiting visit.

Now the two were on-mat rivals. They reveled in the shared animosity — and it spilled into the sauna.

“We really don’t like each other,” Carr recalled. “So I beat Trizzino here at Iowa State. Crazy match. Crazy crowds, of course, back then and we’re going to Iowa — it must have been 70-below wind chill factor. People were all on the floor. There’s no seats. It’s crazy. And I remember, we get there early and I think I have a cowboy hat on. I have like a double-breasted Lone Ranger shirt on with the double buttons. Cowboy boots. So as usual, I’m overweight. So I’m going to work out at the University of Iowa and I go to the sauna. I open the door and I turn my back. I don’t even look, I turn my back, pull it shut and then somebody yells at me: ‘Hey, Carr! Hurry up and shut the door!’ And I turn around and it’s Trizzino. And I was like, ‘Dude, who you talking to?’ So we start wrestling in the sauna before the match! You can’t make this stuff up! So anyway, we wrestled that night. I still beat him. I think I got in trouble. I might have even went to Gable’s corner when Trizzino took a time out. And I did it in the NCAA finals and that’s why one of the officials told me, that’s when they made up the rule that a competitor cannot go to the (opposing) coach’s corner.”

Good rule. Better matches. A-plus showmanship.

The duo proved to be on a season-long collision course and it ended in the finals, just as Carr had planned.

“He’s really strong at the beginning of a match,” Carr said of Trizzino, a three-time All-American. “Big biceps. Big triceps. So he’s pulling me in, grabbing my elbows, because I’m tying up. He’s pulling me in but he’s almost really head-butting me. So I turned to the official and said, ‘Excuse me, sir. Mr. Trizzino is head-butting me. Could you please watch it?’ The guy (ref)— I kid you not — goes, ‘Shut up, Nate!’ So finally (Trizzino) splits my eye open, and I lost it. I lost it. I rushed to the corner and I’m like, ‘Hurry up. Put this gauze on or something to keep it shut. I don’t wanna give him a break.’

“They put it on and before they even could talk to me, they closed it up and as soon as they put that on, I kid you not, I Ieave my corner, go to Gable’s corner and grab Scotty and say, ‘Let’s go.’ Crazy. I pull him back. We wrestle — and then I throw him to his back right after that. And Gable was mad, too, because Gable was like, ‘What are you doing? You can’t be in my corner.’

Carr knew at that point he would not lose that match. Carr, of course, was right.

“He was so good on his feet,” said current Cyclone Head Coach Kevin Dresser, who won a national title wrestling for Iowa in 1986. “So athletic and so powerful. He was fun to watch on his feet and brings a lot of that knowledge to us, that intangible. I can remember, one thing I remember is him blowing kisses to the crowd at Carver-Hawkeye Arena after he won. Every time he won at Carver-Hawkeye Arena he blew kisses to the crowd with a big smile on his face. The thing about Nate is, very rarely is he not smiling.”

He certainly ended the 1981 national tournament all smiles — and atop the podium.

“That second year,” Carr said, “I was a new guy.”

***ANYBODY BUT MONDAY: TITLE TWO***

Carr had relied on sheer determination and a peerless work ethic to win his first title.

He took a different mental approach to achieve the ones to follow.

“After I won as a sophomore, I pretty much pretended like I never won,” Carr said. “I’d start telling myself, ‘Man, I would love to get a national championship. If I did this, it would be incredible.’ So I literally forgot and acted like I’d never won. Then it became like I never won. That changed because (Oklahoma State great) Kenny Monday beat me (in a dual meet) Then it became, ‘I don’t care who wins, as long as Kenny Monday doesn’t win.’”

Carr-Trizzino battles were entertaining.

Carr-Monday clashes would have been well-attended stand-alone events.

They didn’t like each other, either.

Monday followed up his dual meet win over Carr by pinning him for a Big Eight title.

“Anybody, but Monday.” The thought echoed in Carr’s head, but then disaster struck shortly before nationals. Carr had severely injured his elbow, and it looked as if he wouldn’t be able to compete. That second title would probably have to wait.

“I can’t even hold an empty Pepsi can, but they’re putting on this ice, they put a plastic bag, something on me, and I’m like, ‘I don’t think I can wrestle,’” Carr recalled. “So I’m going to talk to coach Nichols — and if you know anything about coach Nichols, he doesn’t say a lot of words and some men grunt instead of talk. So I go to talk to coach Nichols in his office, big office, I go in there, sit down and say, ‘Nick, I need to talk to you.’ So I go in there and sit. I say hi to him, but he’s writing a letter so I’ve gotta wait. So I’m just sitting there. And then he looks up and goes, ‘Uh. What do ya’ need?’ I was like, ‘You know, coach, my elbow’s messed up. I can’t even hold an empty Pepsi can. It’s that bad. It hurts. And I don’t think that I’ll be able to wrestle for this tournament.’ So this might be a week and a half out. I say, ‘I don’t think I’m gonna be able to wrestle. It’s that bad.’ And he just puts his head back down. Writes a couple more lines. So I’m just sitting there and he goes, ‘ENH! You’ll be all right!’ I was like, ‘What?’ So I’m still sitting there. ‘ENH! You’ll be all right.’ And then I left.”

The doc had spoken. A bruised and battered Carr did indeed wrestle — and his path snaked through the field toward an inevitable final showdown with Mr. Monday.

Carr couldn’t contain his energy, his dream. He was amped up and ready to get his hands on Monday.

“My coach, Wille Gadson, is like, ‘Nate, go sit down. Do something. Go relax or something,’” Carr said. “I was like, ‘No. The people here have paid’ — because there were some great matches in ’82 — I said, ‘The people have paid to come watch these matches and I wrestled to get here and watch these matches.’ So I actually want to see the matches. They’re that good.”

“So I’ll never forget saying to myself, ‘The only way Kenny Monday is going to beat me is if my legs are broken, my neck is broken, my arms are broken.’ And they called my name at Iowa State and I had to go through the (raised) swords — they had the swords you had to run through, a National Guard line — and they were like, ‘Nate Carr,’ and I tell you what, a spirit must have left me. … And then we battled. It was crazy. I won in overtime.”

He did it with grit. Panache. With a dreamer’s stubborn desire that would wobble or waver.

“We threw down,” Carr said. “Because that dude is not backing off, I’m gonna tell you this. And I’m definitely not gonna back off either. So I beat him. I was happy. We had words even after that. Like, ‘I’m getting you.’ His mom even told me: ‘We’re gonna get you, son.’ She did. She was a competitor. We were at this gathering after that. I was with Willie Gadson and evidently, Kenny Monday’s there, his mom is there and she’s like, ‘Ooh, we’re gettin’ you!’ And Willie Gadson just said something like, ‘Ma’am. I think your son better go to another weight.’ Then we end up wrestling again!”

**MO’ MONDAY, NO PROBLEMS: TITLE THREE***

Monday beat Carr once again in the Big Eight finals.

“I think I only got taken down once that year and it was by him,” Carr said.

The future Olympic gold medalist gloated. Carr smiled. “Anybody but Monday.”

“We have words again. I told him something like, ‘You can have all those Big Eight titles you want,” Carr said. “I just want the other one.”

Carr’s focus became laser-like.

“I am ready,” he constantly told himself.

He read voraciously.

“Linda makes a book that says, ‘On your way to your third national title,’” Carr said. “And it has Bible verses in it and then, of course, I’ve got quotes from Dan Gable. And one thing I realized is anytime somebody says something good about you and you like it, you should collect it, capture it and use it. Because one reporter said, ‘Nate Carr was so awesome last night, that he had his opponent in one hand and the crowd in the other.’ I liked it. So that was my mantra. Gable would pull one card out of the deck and whatever number it was he’d double it in pushups. Gable was intense. ‘Wrestling is like a chain. A chain goes from link to link. Wrestling you go from move to move. You are unstoppable.’ So I am reading this stuff thousands of times for this championship.”

Carr arrives at nationals strong, eager and well-trained. He’s also, as usual, overweight.

The second weigh-in time comes. Carr, once again, is overweight, but by a wider margin.

“I’m over 13 1/2 pounds with two and a half hours left in the weigh-in (process),” Carr said. “Kenny Monday is over 6 1/2. So, my coaches, they’re on me. They’re working me. So I had to make a short-term goal: Lose the 13 1/2 before Kenny loses the 6 1/2. And I did it.”

He didn’t need a sauna scrap to do it, either.

But, how?

“I was in great shape,” Carr said. “And I trained myself to do it.”

He also trained to become tireless. Literally. He worked out so hard — and with such quality training partners — he would not experience fatigue.

“What I told myself mentally was, ‘If you work out two and a half hours wrestling tough guys — top guys in the country — it literally is impossible for you to get tired in seven minutes,’” Carr said. “And that was my trick: Impossible for me to get tired in seven minutes. So I used that. I could work out and let you watch me. Now you’ve got another thing comin’ if you think I’m gonna get tired. So I literally trained to compete, no matter what, without getting tired or being scared. That was one of my tricks.”

Also, there was that ever-present “Anybody but Monday” tactic.

“I worked hard because every time I stopped, I saw him getting his hand raised,” Carr said. “I was like, ‘Oh, that can’t happen. That can’t happen.’”

It didn’t, but it wasn’t looking good early for Carr.

“He wrestled great,” Carr said. “He’s winning. I’m not afraid to say he outwrestled me. I don’t know. I might use Muhammad Ali’s term — I rope-a-doped him, but he was going hard. I kind of got through the battle. I just do enough. There’s like 30 second left, a short time. He’s already been warned for stalling. He’s winning by one and took a break. That’s on him. I don’t know why he took a break — probably was tired, but he took a break and when he took the break, I said to myself, ‘Either I’m taking him down, or he’s getting called for stalling. Those are the only two choices.’ So when he came back after the injury time out, I went psycho. Boom! And they called him. Now we’re going overtime for the second time! And I kid you not, So I’m dripping sweat, going back to the corner. Chris Campbell’s there. Willie Gadson.”

Everyone, it seemed was in Carr’s corner. Guys he’d relied on to build and learn. Guys who had helped him every step of the way — and would again.

“I sit down in the chair and Chris Campbell says this to me: ‘This is incredible,’” Carr said. “This is right where you wanna be!’ He’s referring to last year — and it clicked. I was like, ‘Huh- ah, yeah!’ Boom! Go out in overtime and I win 5-2. Crazy.”

Carr and Monday once again “had words.” But as Carr triumphantly trudged to the locker room, Monday chased him down to ask a question.

“You wrestling freestyle?” Monday asked, in reference to training for the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea.

Yes, he was.

And that’s how rivals turned into training partners and friends. Monday earned the gold medal at 74 kilograms. Carr cut some weight and clutched bronze in 68 kg.

“We’re friends now, but back in the day,” Carr said. “Yeah.”

***MORE DREAMERS***

Carr believes his life, in a sense, has come full circle. He’s been training former ISU standout and national champion Kyven Gadson for international competition. Kyven’s dad, the late Willie Gadson, helped train him to achieve national titles and international medals. It feels right to be in Ames. Maybe even dream-like.

“I look at him and I see his dad,” Carr said. “And Kyven’s such a great kid and his dad helped me. His dad was the best man in my wedding. We were close and I actually ended up leading him to Christ and not only that, I did his eulogy. So it’s just more of like destiny. Almost like destiny. Like, for sure, I am supposed to be right here, right now, at this time. It just happened to be a surge. Of all the places I could go help, this is the best place. And Dresser — I think that all ended up working out good. My son, he definitely saw the legacy. Definitely, he loved the coaches and I think, third, he’s a dreamer. And of course, Kyven is as well.”

Carr’s connection to ISU started with Carr’s mom’s dream. It continues through him, and now David. Where will it lead? The Carrs smile at the array of opportunities.

“My dad’s super humble,” said David Carr, who will compete at 74 kilograms for the U.S. Junior World Team during August’s Junior World Championships in Tallinn, Estonia. “He was so humble that I think I didn’t really understand, coming up in wrestling, I didn’t really understand how good he was until maybe fifth or sixth grade. I went to a camp and started going to camps with people and they’re like, ‘Dude, your dad’s a legend. He’s an Olympian and three-time (national champ).’ I really didn’t understand that because my dad’s so humble. He doesn’t really go out and tell people that. He’ll just keep stuff — trophies — in his garage and won’t even look at it.”

Past goals become a concrete reality. Trophies reflect that. Dreams don’t. They defy reality and bend perception. Just like Carr’s parents did when they established roots in Erie and flourished through faith and hard work.

“The main thing was they loved us,” Nate said. “Never doubted it. Always sensed their love in me — even when I was in college. Say I lost to Kenny Monday, I’d call my mom and say, ‘Hey mom, I just lost to Kenny Monday.’ My mom’s first thing: ‘Are you reading your Bible?’ I’m like, ‘What?’ And then when the conversation’s getting ready to end, she’d say, ‘Ah, you’ll get him next time.’”